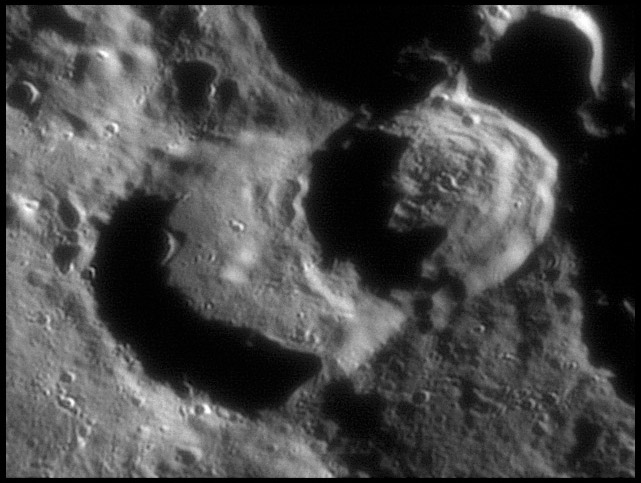

image by Damian Peach

Huggins is the bigger one, 65 km in diameter, and Nasireddin (52 km) is obviously younger since it breaks the older crater’s rim. This illustrates superposition, one of the basic laws of geology. The rest of what we see in this infrequently imaged pair is a softness of the rims, indicative of slow aging by micrometeorite abrasion. Nasireddin is large enough that a single significant central peak might be expected, but instead it hosts six or more small hills, one of which might be the main peak. The walls, under the high scarp, are little terraced, and a second major fault scarp drops them down to the floor. But look outside Nasireddin’s rim to learn something interesting. Whereas the external wall of Nasireddin is minimal to the south, notice how laterally extensive it is on the floor of Huggins. Material associated with Nasireddin actually engulfs the remnant central peaks of Huggins. This wall expanded further because there was no resisting surrounding rock to contain it. So the wall of Nasireddin expanded to the west into a depression - the floor of Huggins. If you think this is interesting look at what Nasireddin did to Miller, the entirely shadowed crater immediately north. To see that someone needs to send LPOD a great image where Miller is seen under a higher Sun… Who said the central highlands are boring?

Technical Details:

13 October, 2006, C14″ Schmidt Cassegrain. Lumenera LU075M CCD camera.

Related Links:

Rükl chart 65

Damian’s website

A regional view

COMMENTS?

Click on this icon File:PostIcon.jpg at the upper right to post a comment.